One of the longest highways in the United States is Interstate 40. Spanning more than 2,500 miles, it passes through eight states, from North Carolina to California. Weaving its way through cities, counties and landscapes that have very little in common except for the highway that connects them.

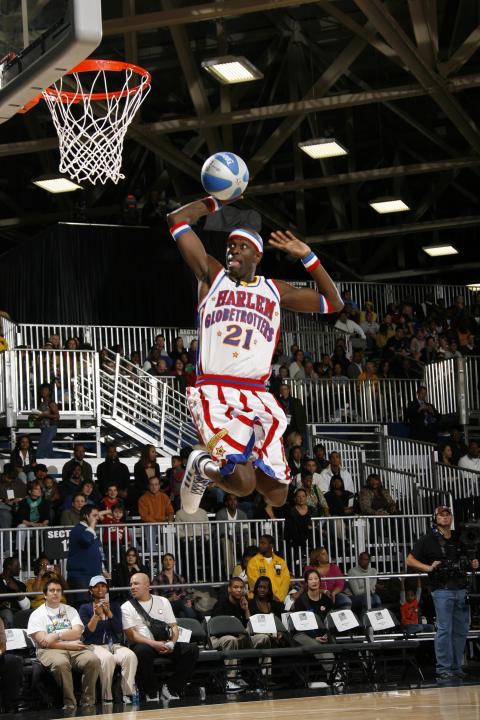

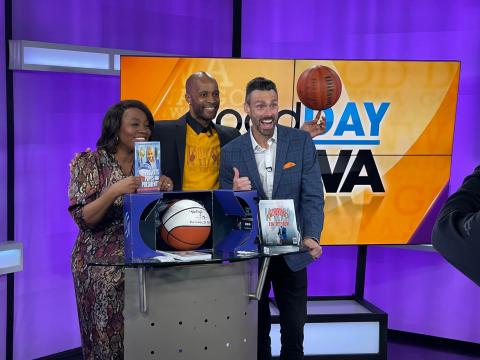

Midway between Memphis, Tennessee and Little Rock, Arkansas, Interstate 40 passes through a town with a population of just over 2,500 people. Originally founded as a railroad town in 1872, Brinkley, Arkansas, is known as a transportation and agricultural center, but for Herbert Lang, it’s home. It’s there he first learned the lesson that would serve as his own version of the interstate next to his town – connecting events in his life that didn’t innately have much in common: a college basketball scholarship, nearly two decades as a Harlem Globetrotter and a career as a motivational speaker.

These things may seem as different as North Carolina is from California, but for Lang, they connected because of the one truth he learned early on the streets of Brinkley: kindness is free.