When retired NBA players attend All-Star Weekend in Salt Lake City and swap stories about their time in the league, there will undoubtedly be tales about the rookie hazing they dished out and endured.

But Adrian Dantley will not have stories that align with that piece of NBA culture.

From the time he entered the NBA in 1976, he refused to participate in the initiation ritual, even when it came to John Stockton and Karl Malone.

“When I was a rookie in Buffalo, somebody told me to carry the bags from the bus to the hotel,” Dantley recalled. “I told him: ‘I’ll tell you what: We play a game of one-on-one, and the loser carries the winner’s bags,’ and that put an end to that.”

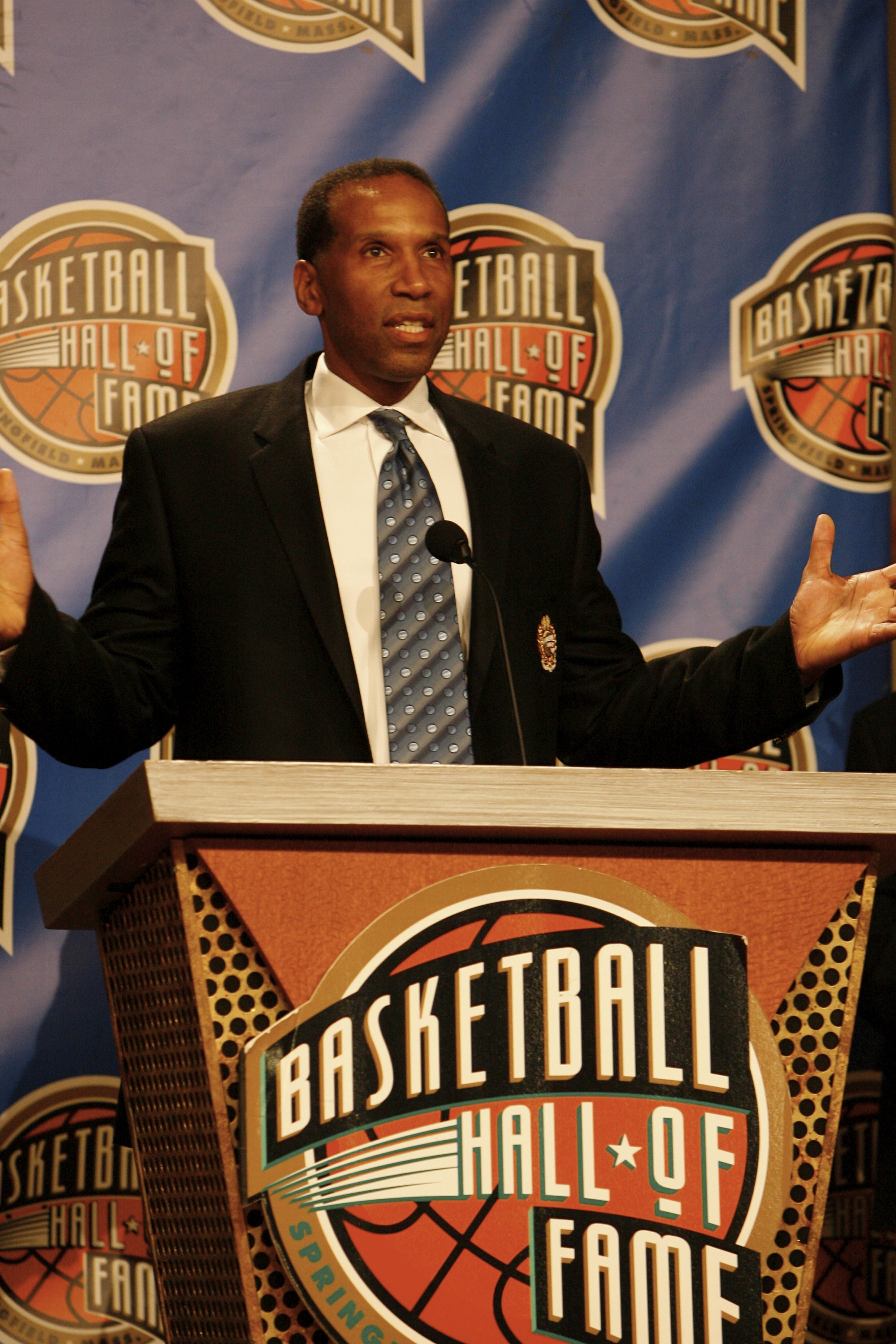

Dantley, who spent 17 seasons in the NBA before finishing his pro career with one season in Italy, was a six-time All-Star who averaged at least 30 points in four of his seven seasons with the Jazz. Like the dynamic the Thunder have in Oklahoma City, the Grizzlies in Memphis and the Kings in Sacramento, when your team is the only professional sports show in town, the fan base is loyal and rabid.

That is how Dantley, who will turn 68 on the final day of February, remembers Salt Lake City.

“Of all the cities where I played, that was my favorite,” he told Legends Magazine in a telephone interview in mid-January from his home in Maryland. “Other players would come into town and ask what there was to do, and I said I really didn’t care because I was too busy working out and playing ball. I didn’t need anywhere to go. I just wanted to get minutes.”